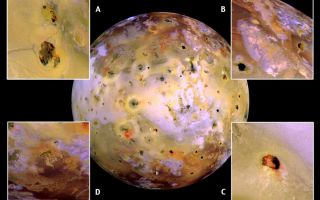

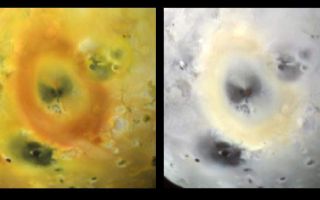

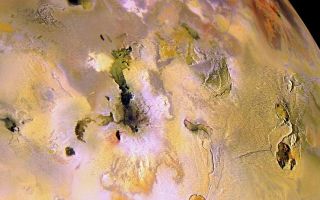

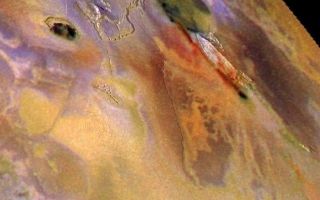

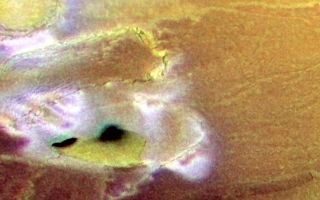

PIA02319: Closeups of Io (false color)

|

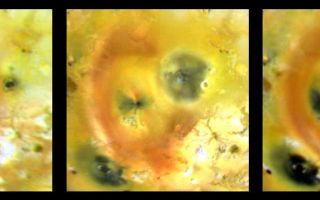

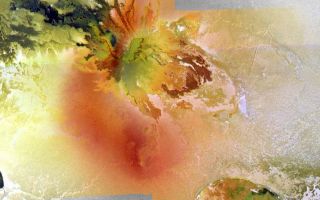

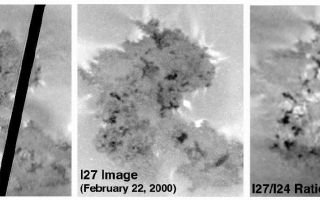

PIA02501: Changes at Pillan Patera

|

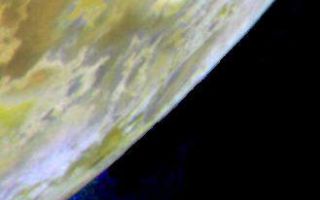

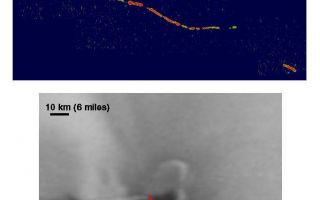

PIA02502: Masubi Plume on Io

|

PIA02503: Migrating Volcanic Plumes on Io

|

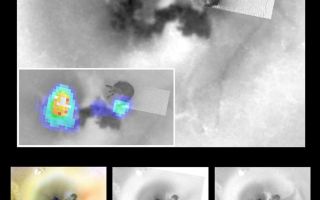

PIA02504: Close-up of Zamama, Io (color)

|

PIA02505: Close-up of Prometheus, Io (color)

|

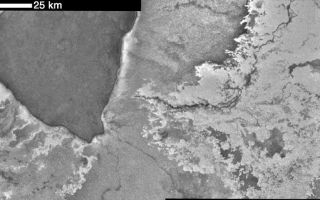

PIA02506: Amirani-Maui: Longest Known Active Lava Flow in the Solar System

|

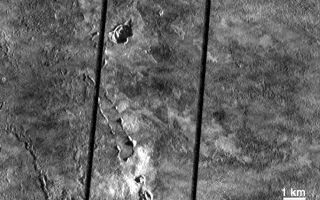

PIA02507: Highest Resolution Image Ever Obtained of Io

|

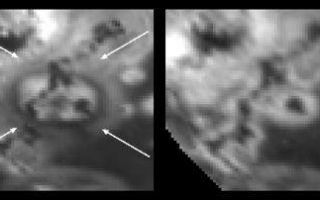

PIA02508: Galileo discovers caldera at Prometheus Volcano, Io

|

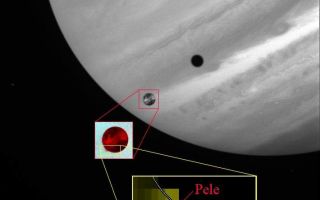

PIA02510: Pele's glow

|

PIA02511: Pele's Hot Caldera Margin

|

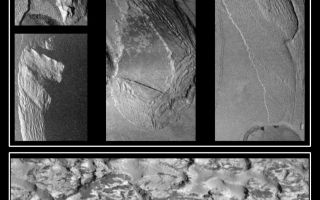

PIA02512: Ongoing Geologic Activity at Prometheus Volcano, Io

|

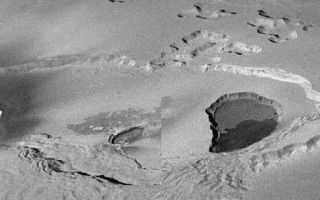

PIA02513: Collapsing Mountains on Io

|

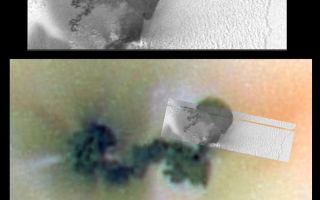

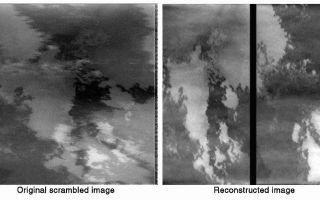

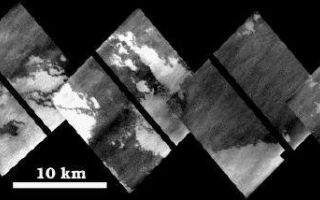

PIA02517: Reconstruction of Scrambled Io Images

|

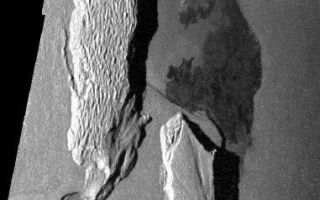

PIA02518: Bright Channelized Lava Flows on Io

|

PIA02519: Lava Fountains on Io

|

PIA02520: Mountains on Io

|

PIA02522: Earth-Based Observations of a Fire Fountain on Io

|

PIA02523: Earth-based images of the Fall 1999 Loki Eruption

|

PIA02526: Ionian Mountains and Calderas, in Color

|

PIA02527: Zal Patera, Io, in color

|

PIA02534: Terrain near Io's south pole, in color

|

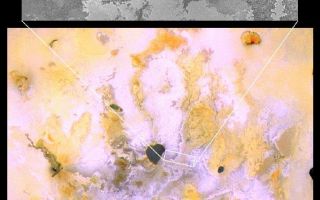

PIA02535: Culann Patera, Io, in false color

|

PIA02536: 1997 Lava Flows Near Pillan Patera, Io

|

PIA02537: Lava Flows at Zamama, Io

|

PIA02538: Changes Observed in Just 4.5 Months at Prometheus, Io

|

PIA02539: Bright Lava Flows at Emakong Patera, Io

|

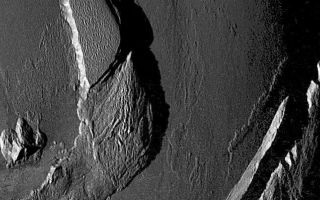

PIA02540: Rifting at Hi'iaka Patera, Io?

|

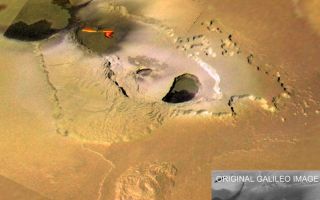

PIA02545: Eruption at Tvashtar Catena, Io, in color

|

PIA02546: Sulfur Gas in Pele's Plume

|